Economic outlook: weakness and divergence ahead

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the opening of PIMCO’s London office. Today, the U.K. is the second-largest asset management center in the world and home to PIMCO’s second-largest trade floor, underscoring the importance of our international client base. London is our headquarters for the Europe, Middle East, and Africa (EMEA) region, which has grown to include eight offices.

Hosting the Cyclical Forum outside of the U.S. for the first time advanced some key objectives of our forum process, such as fostering a global mindset and challenging our own assumptions and biases.

A year ago, the U.K. liability-driven investment (LDI) market faced a crisis that started when the British government proposed unfunded spending increases. That led to a sell-off in U.K. sovereign bonds, known as gilts, and caused the British pound to tumble.

In our June 2023 Secular Outlook, “The Aftershock Economy,” we said the LDI crisis could be a canary in the coal mine for long-term fiscal issues globally. This is particularly relevant now, as governments worldwide grapple with growing debt burdens. That includes the U.S., the world’s largest issuer of sovereign bonds, which in August was stripped of its AAA credit rating by Fitch. During our forum, we were fortunate to have Sir Charles Bean, the former deputy governor for monetary policy at the BOE, as a guest speaker as we discussed these and other issues.

While the location helped shine a brighter spotlight on markets outside of the U.S., we used our Cyclical Forum as we always do: to discuss the latest opportunities and risks across the economic and investment landscape, and to develop a six- to 12-month outlook. We emerged with five key economic themes.

1) Resilience and fiscal support to fade as monetary drag kicks in

Milton Friedman said monetary policy acts with “long and variable lags.” We think the same can also be said of fiscal policy. Economic resilience this year owed much to fiscal support, with the U.S. deficit widening and with households having ample savings from pandemic-related stimulus.

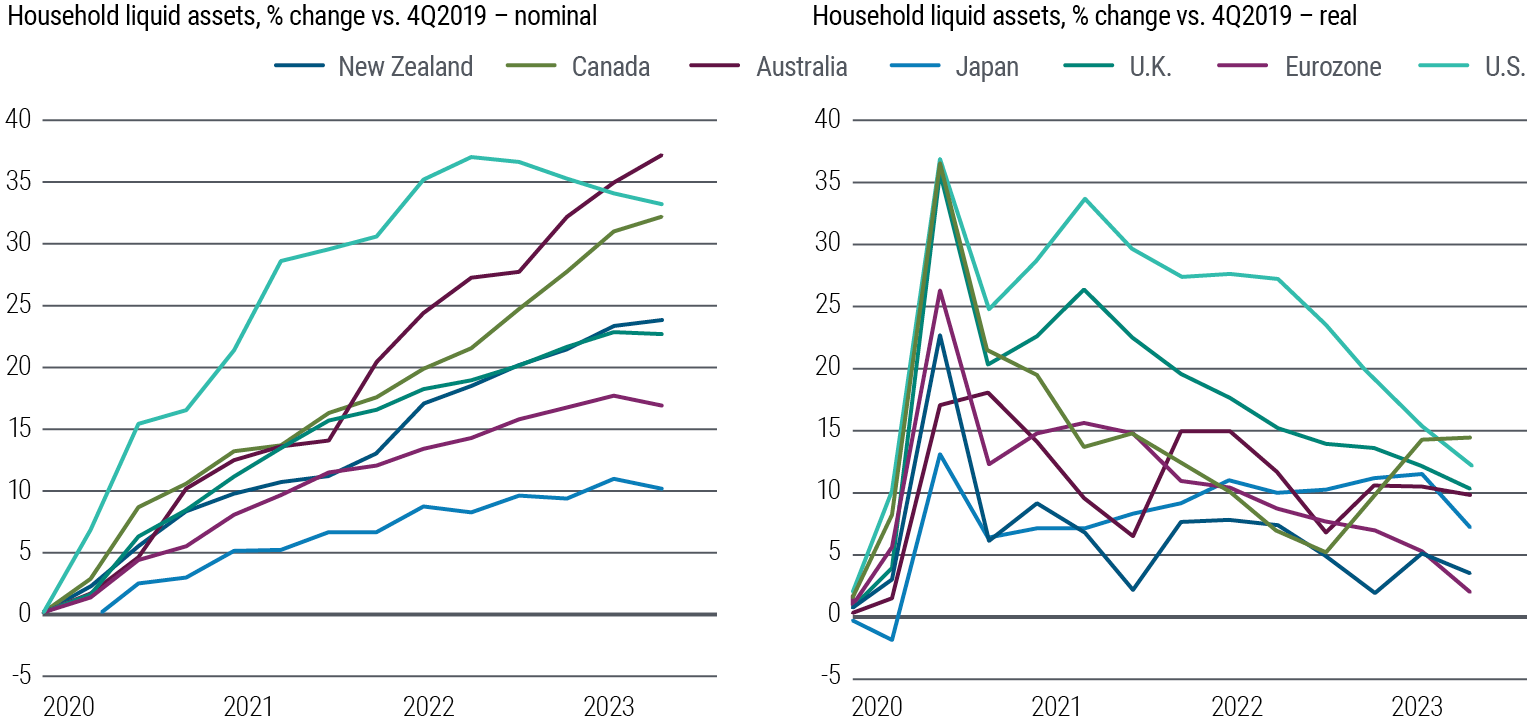

This support looks set to diminish. U.S. fiscal policy will turn contractionary, while recent elevated inflation erodes the real value of wealth, including the excess savings accumulated as a result of government payments to households during the pandemic. Our analysis suggests that household liquid assets built up during the pandemic (see Figure 1) will likely deplete in real terms over our cyclical horizon.

Figure 1: Household liquid assets across DM economies look set to diminish in real terms following post-pandemic peaks

As fiscal support fades, the drag from tighter monetary policy will intensify. As we noted in our Secular Outlook, any future fiscal support may also be constrained due to high debt levels and the role of post-pandemic stimulus in fueling inflation.

Granted, there are factors that could weaken the impact of monetary policy this time. The private sector holds substantial cash that is earning high interest rates. This is also the first major tightening cycle in which central banks are paying interest on reserves.

An inverted yield curve, with short-term debt yielding more than long-term bonds, benefits net interest income for households, which tend to have short-duration assets and long liabilities.

Additionally, households and businesses have extended the maturity of their debts, resulting in a more gradual pass-through of rising interest rates. Central banks’ significant purchases of fixed income assets mean that governments are also absorbing a larger share of recent bond price losses.

Still, we believe economic weakness is coming. We expect unemployment to rise next year, leading to a normalization of central bank rates back toward neutral levels.

2) Growth and inflation have peaked

The global economy, led by the U.S., has shown remarkable resilience despite one of the most rapid tightening cycles in modern history, raising questions about the effectiveness of monetary policy.

We discussed whether monetary policy lags might be longer as a result of the pandemic and the related policy response, or whether more tightening is needed, perhaps because the neutral real long-run policy rate has risen. (That neutral rate, or r*, is the estimated interest rate that over time is consistent with the economy operating at capacity and target inflation.)

Our view is that it is mostly a lag. We believe growth has peaked. We expect resilience to turn into weakness as growth slows later this year and into 2024.

Fiscal headwinds – especially in the U.S. – will soon come into play. We think that monetary policy is still working, as evident in a clear slowing in credit growth and a meaningful tightening in bank lending standards.

We expect resilience to give way to weakness as global growth slows later this year and into 2024.

We believe inflation has peaked as well. In most DM economies, both headline and core inflation have decreased from their highs, albeit at different rates. Sticky wage inflation is likely to support core inflation longer unless there is some weakness in the labor market. We forecast core inflation in the 2.5%–3% area in the U.S. and Europe at the end of 2024. We anticipate that falling growth and rising unemployment will lead to more disinflation, helped also by other factors (for more, please see our Viewpoint, “Fiscal Arithmetic and the Global Inflation Outlook”).

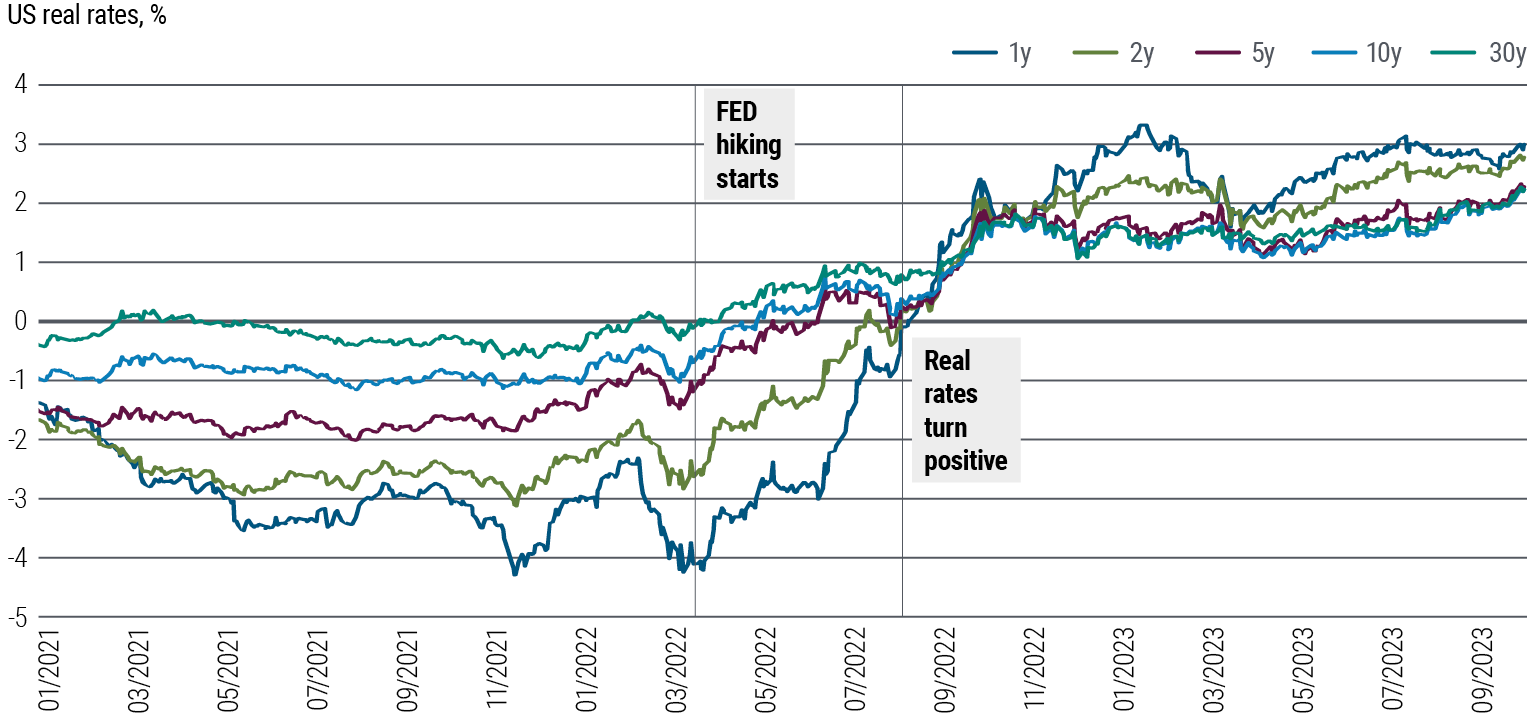

Figure 2: U.S. real rates have been above zero only since late 2022

3) A soft landing would be an anomaly

It’s worth noting the historical rarity of central banks achieving a soft landing – or avoiding a recession – when inflation is high at the start of a cycle.

We analyzed 140 tightening cycles across developed markets from the 1960s through today. When central banks hiked policy rates by 400 basis points (bps) or more – as several have done this cycle, including the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed), the European Central Bank (ECB), and the BOE – almost all such instances ended in recession.

Notably, better economic outcomes in the face of past hiking cycles were often associated with supply expansion. The post-pandemic supply-chain normalization could help here, as well as a possible AI-fueled productivity boom. However, it’s yet to be seen how much these factors contribute to boosting productivity over our cyclical horizon.

Healthy starting conditions for household and corporate balance sheets, as well as proactive financial stability policies – think of the BOE’s intervention in the LDI crisis, or the U.S. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation quickly extending bank guarantees under exceptional circumstances earlier this year – could be another source of assistance. These policies have so far successfully thwarted a recession.

But history suggests that tight financial conditions create a high risk of financial market accidents, and there are areas of vulnerability within markets, such as in private credit, commercial real estate, and bank loans.

There are also risks related to China. The country’s recovery has been weaker than expected, weighed down by the property market. Housing investment, which had been expected to stabilize, is down 7.5% year-over-year as of August, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

More stimulus is likely needed to stabilize China's property sector and the economy more broadly. There are risks if stimulus is insufficient or too slow to arrive. In a downside scenario, growth could further decelerate in 2024 (to 3%, versus our current baseline of 4.4%). This would suppress China’s demand for global goods and services, weighing on the global economy.

The government still has the capacity and tools to avoid such a downside scenario. We expect continued policy easing to support growth.

More fiscal supports, including a wider central government deficit and higher local government special bond issuance, could help lift domestic demand via infrastructure capital spending or tax cuts. We believe further reduction to China’s policy rate, currently at 2.65%, is likely. The government has recently called for more countercyclical macro policies to prevent the economy from sharp deceleration.

4) Recession risk appears to be higher than markets are pricing

Our baseline implies growth underperforming and inflation falling. Markets, and risk assets in particular, appear to be priced for an “immaculate disinflation” scenario, in which growth remains solid and core inflation drifts toward central bank targets fairly swiftly. We think such pricing may reflect complacency.

We see growth in DM economies falling to varying degrees in coming quarters, with the most interest rate sensitive faring the worst. Europe and the U.K. also look vulnerable due to trade links with China and the lingering effects of the energy shock to terms of trade and investment. U.S. growth also looks set to slow, hovering between stagnation and mild recession.

We see unemployment rates rising by more than both consensus and central banks anticipate – by about one percentage point in the U.S. and just shy of that in Europe.

5) Monetary paths set to diverge

The extent of this expected slowdown remains uncertain and will vary across economies.

The relatively gradual decline in inflation means that central banks are unlikely to come to the rescue quickly to revive growth. Major central banks – including the Fed, the ECB, and the BOE – are at or very near the end of their tightening cycles, in our view, but will likely proceed cautiously with rate cuts given their mandates to control inflation.

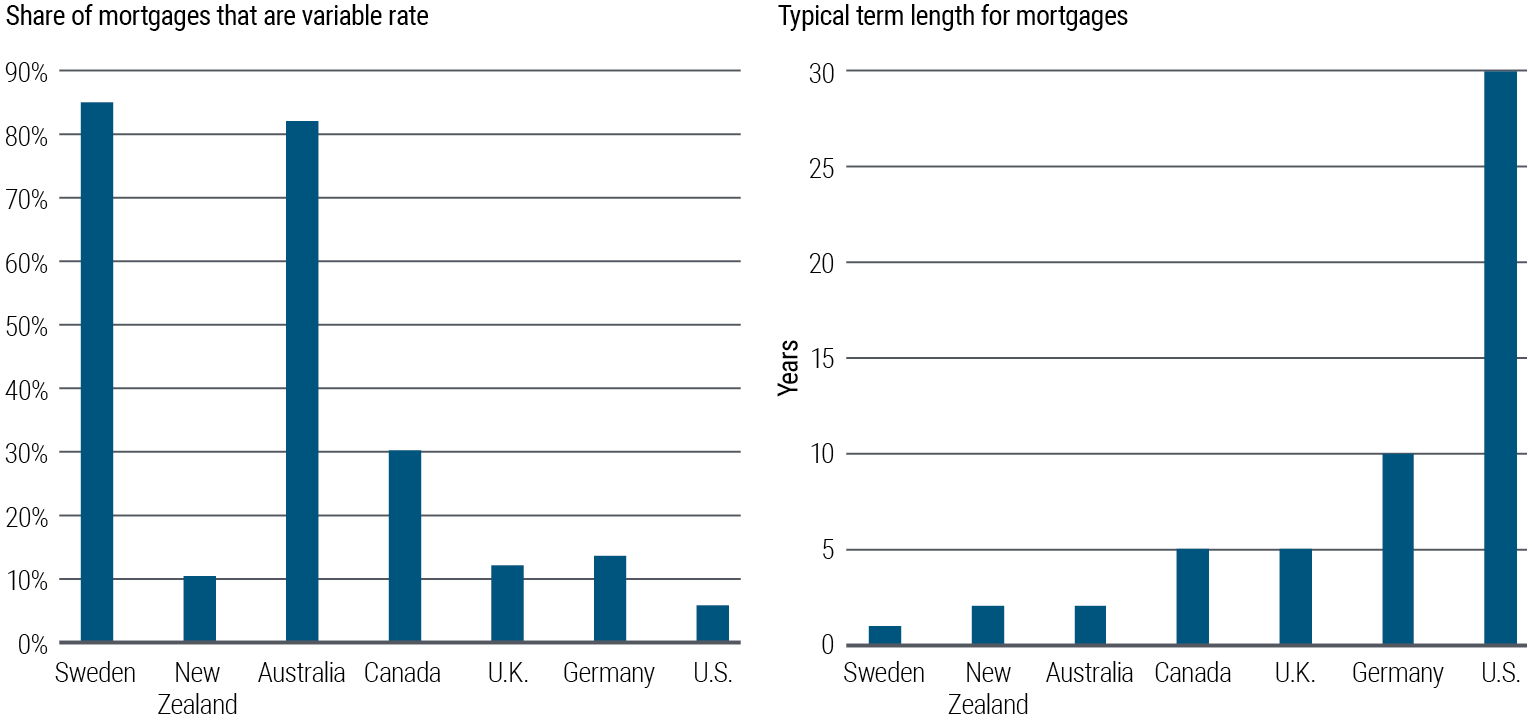

We see plenty of room for monetary policy divergence. More rate-sensitive economies such as Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, which have generally higher household debt and a higher share of variable-rate mortgages (see Figure 3), may get hit harder. We see potential there for faster rate normalization than what market pricing suggests.

Figure 3: Mortgage structure can vary greatly across countries

Elsewhere, we see the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) continuing to cut its policy rate, albeit only modestly. We see the Bank of Japan (BOJ) bucking the trend and raising its policy rate next year given a higher inflation trend compared with the past.

In emerging markets (EM), we see scope for a great deal of differentiation, with the more orthodox group of central banks, such as those in Brazil and Mexico, that hiked early (in many cases ahead of the Fed) able to ease policy relatively quickly. We see several other central banks, such as those in Poland and Turkey, being more constrained.